Should we love or hate space rocks?

To fully enjoy reading this post, listen to The Golden Age by The Asteroids Galaxy Tour and to Space Rock by Rockets. Ideally, treat yourself and enjoy both, one after the other…

Resources, resources, we are always looking for resources to make any kind of things. However, resources are limited, especially in a limited environment like our planet. Recycling and circular economy are for sure terrific strategies to limit our insatiable hunger, but they are not enough. So, where could we find new resources before we run out of them? Simple, just looking up to the sky, there is plenty of material in space!

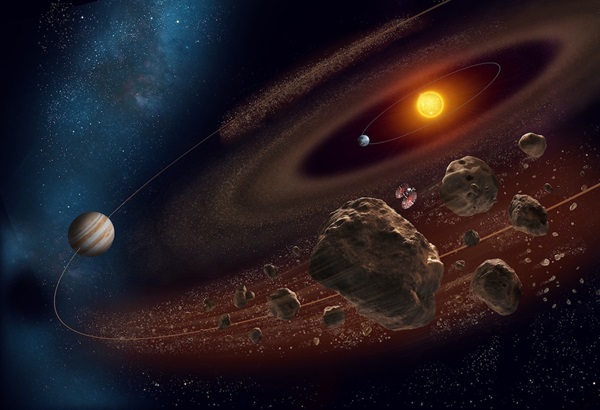

Asteroids are basically rocks spread over the Solar System, orbiting around the Sun, the big attractor. Why are they there? In a few words, planets were formed starting from a primordial cloud of gas and dust orbiting around our star, aggregating because of gravity. Not all material ended up forming large planets, but some of it remained scattered out there forming smaller items, like dwarf planets (such as lovely Pluto) and, of course, asteroids.

To give you an example, think about a LEGO construction, you built at least one in your life, didn’t you? Asteroids are like the left-over pieces once you finish the construction: you completed the project following the instructions (the planets), however, those pieces remained in your hands (the asteroids).

As well as those LEGO pieces, asteroids can be useful to build something else! This is the idea behind asteroid mining, a theoretical concept starting to become more and more concrete in the recent years.

Before rushing to it, let’s have a closer look at our space nuggets, to understand better why mining them could be a great opportunity. First of all, they are categorized according to their composition, in three major types:

- C-Type or carbonaceous, the most common, they are very dark objects containing mainly carbon, clay, silicate rocks, even a good percentage of water in the form of hydrated minerals and ice, like a dirty chunk of stone coal;

- S-Type or silicaceous, proper stones that are made up mainly of silicate materials based on iron and magnesium;

- M-Type or metallic, the most rare and desirable nuggets, made mainly of nickel-iron minerals, very often accompanied by other precious metals, such as gold, platinum and rare earths.

In addition to these three main groups, there are also several subcategories, some even consisting of a single asteroid, somewhat different from all the others.

Another way to classify asteroid is based on their position in the Solar System. We have:

- Near Earth Asteroids, or NEA, objects whose circles around the Sun sometimes bring them close to the Earth; they are divided, in turn, in subcategories depending on the shape of their orbit (Amor, Apollo, Aten);

- Trojans, special objects, parked in particular points of a major planet orbit (Lagrange points), allowing them to follow or precede at the same distance from the planet itself during its trip around the Sun; the name “Trojans” was chosen because the first discovered asteroids in this group were identified with the names of heroes from Homer’s Iliad; the most numerous are Jupiter’s ones;

- Main Belt Asteroids, located between the orbit of Mars and Jupiter, they form the largest group of this classification, and they are what remains of a planet that never formed or exploded in the very early stages of its formation (there is still no definitive theory about it, even if nowadays the “never formed planet” is the most accredited);

- Centaurs, small group of objects which are spread out between Jupiter and Neptune, more similar in composition to comet nuclei (more ice than minerals);

- Kuiper Belt Objects, or Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNO), large group over Neptune orbit, full of frozen stony objects but also dwarf planets like Pluto.

One could ask, what about the Oort Cloud? Isn’t there a group of asteroids in the great suburbs of our Solar System? The answer is “we don’t know”, the Oort Cloud is so far away that we are not sure what it is made of. Only occasionally we have been in contact with the “visitors” coming from there, the long period comets. This is why the Oort Cloud is also known as the House of Comets.

At this point another question could arise: is there a relationship between comets and asteroids? We could say that they are somewhat like cousins, belonging to the same kind of cosmic fragments. However, there are differences: comets are almost like dusty snowballs, whilst asteroids are like stones, as seen above. Comets are also characterized by having a coma and one (or more) trail, whilst asteroids do not exhibit such features. They could also differ in their orbit shape which is usually more eccentric and elongated for comets. On the other hand, sometimes the distinction between comets and asteroids can become very “subtle”, and there are objects that can even move from one group to the other, like Centaurs themselves.

Let’s keep comets aside for a moment, ready to pick them up again when we will explore mining, since they are very rich in what will be like oil for space economy: water.

How do we know all this about our beloved rocks? First of all, scientists have been observing them with telescopes of all kinds since the discovery of the first asteroid, Ceres, which took place on the 1st of January 1801 by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Piazzi. Since then, more than eight hundred thousand asteroids have been discovered, analyzed, and catalogued. Despite running for two centuries, the task of discovering asteroids is just at the beginning: it is estimated that in the Solar System there are zillions of asteroids larger than 100 meters!

Obviously, we didn’t just observe asteroids with telescopes, we also sent spacecrafts to visit them closely, and even touch them. The first fly-by was made by the famous American probe Galileo, whose main objective was to study Jupiter and its moons. During its trip to Jupiter in 1991, the spacecraft passed a few thousand miles from 951 Gaspra, a gorgeous stony asteroid in the Main Belt, taking the first incredible closeups of this new world. The first mission entirely dedicated to study an asteroid was NEAR Shoemaker, a spacecraft full of instruments that scanned 433 Eros, a huge stony NEA, king of records: first NEA discovered, first orbited and first even touched by a spacecraft. We then had other very enthralling missions like the European Rosetta, orbiting and touching Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (remember to bear comets in mind!), and the Japanese Hayabusa, able to return back to Earth a small sample of another stony NEA, 25143 Itokawa.

At this very moment, there are two spacecrafts in action, sent out to analyze, orbit around, touch and return a sample of two other NEAs. The first is the Japanese Hayabusa-2 and its objective is 162173 Ryugu. The other is NASA OSIRIS-REx, aimed to visit 101955 Bennu. OSIRIS-REx has already collected the sampling successfully and it will depart from Bennu in 2021, returning to Earth in September 2024, while Hayabusa-2 has returned the sample of Ryugu back to Earth just… today (this article is published the 6th of December 2020, Australian Time, just after sample’s touchdown)!

Let’s celebrate such an incredible success! We are living in very exciting times and every day we can witness the first signs of a new Golden Age, the age of the Spacepolitans! So, let’s take a break to party and shout loud the Spacepolitans motto: “Space for All, All for Space!”.

Oh, I almost forgot! We are not done here with asteroids! In the next entry we explore how they could be the potential incipit of our journey amongst the stars (asteroid mining), but also how they could prevent it (asteroid threat)… after all, they are our cosmic cross and delight!

2 thoughts on “Asteroids: Cross And Delight (1/2)”