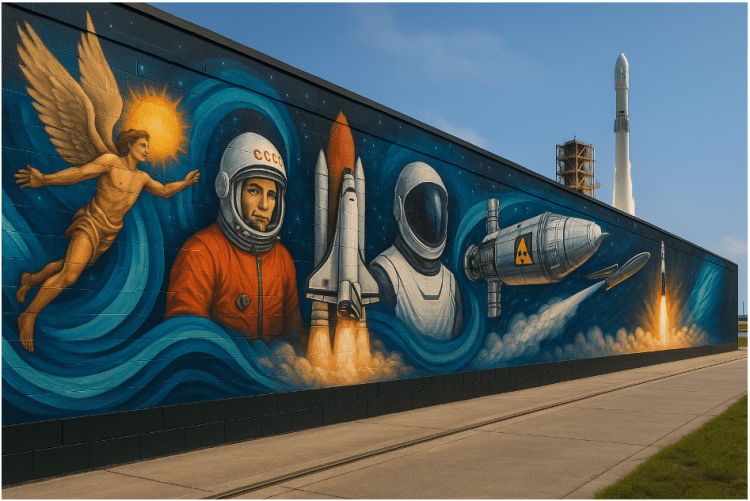

Myths, machines, and minds behind space travel: from the past we built, to the rockets we fly, to the futures we dare.

Listen to Ballata by Litfiba, Planet Caravan by Black Sabbath, Breakthru by Queen, and Space Travel by Black Eye to enjoy reading this page.

Crossing the Threshold

Space, the last frontier. But where does this frontier actually begin? How far above Earth do we say “space” starts?

There is no single legal boundary for space. The definition is rooted in the work of Theodore von Kármán, the engineer who calculated the altitude at which the atmosphere becomes too thin for conventional flight, approximately 83.6 km above sea level.

From his studies came the idea of a traditional boundary: the Kármán Line, fixed at 100 km and adopted by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Others, like the United States, award astronaut wings starting from 80 km (50 miles).

One hundred kilometers may not sound much, but on a vertical scale, it is immense: more than twelve Mount Everests stacked one on top of the other. And yet, this is only the threshold. The real challenge is not where space begins, but how we get there and beyond.

From Imagination to Ignition

Mythology offers one of the earliest tales of human flight: the story of Icarus, who attempted to reach the Sun on wings made of wax and feathers. Today we know, thanks to Kármán’s studies, that his fall would not have been caused by heat alone, but by the thinning air at altitude, a less poetic but more realistic barrier. Icarus was not the first human in space, yet his daring attempt remains a powerful metaphor for our yearning to reach for the stars.

Centuries later, science fiction gave that dream a new form. In 1865, Jules Verne, in his novel “From the Earth to the Moon: A Direct Route in 97 Hours, 20 Minutes”, imagined launching a crew toward the Moon inside a giant cannon shell. Verne’s concept, grounded in calculations, was audacious and nearly prescient. In practice, such a shot would have pulverized its passengers into a “human smoothie” from the immense acceleration, but the principle pointed in the right direction. True access to space would indeed come through powerful projectiles, though refined into a gentler and more elegant technology: the rocket.

The very word “rocket” comes from the Italian “rocchetto” (little spindle), after its shape. Yet the earliest rockets appeared much earlier, in 13th-century China, fueled by gunpowder and used both in war and in fireworks. For centuries, that role remained largely unchanged. Then, in 1861, William Leitch, a Scottish astronomer, was the first to suggest rockets as a means for human spaceflight. His intuition paved the way for a generation of pioneers at the dawn of the 20th century: Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, Robert Esnault-Pelterie, Hermann Oberth, and Robert H. Goddard, thinkers who transformed rockets from weapons and fireworks into the vehicles that would one day ignite humanity’s path to the stars.

The First Space Age

The theories of the pioneers soon became practice, igniting the Soviet–American Space Race of the 1950s and 1960s. At its heart was Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, the Chief Engineer behind the Soviet “firsts”:

- Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, was launched on October 4, 1957, by the R-7 rocket.

- Laika, the first animal in orbit, on November 3, 1957.

- Yuri Gagarin, the first human in orbit, April 12, 1961, aboard Vostok 1.

- Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in orbit, June 16, 1963, on Vostok 6.

- Alexei Leonov, the first to perform a spacewalk, on March 18, 1965, on Voskhod 2.

An extraordinary string of achievements, all riding on variants of the R-7, carried humanity beyond the symbolic “Pillars of the Kármán Line”.

An impressive list of records: the combination of rocket and spacecraft finally allowed men to pass the cosmic Pillars of the Kármán Line!

The United States caught up under the controversial genius of Wernher von Braun. A student of Oberth and later designer of the V-2, he was brought to America after World War II along with his team of engineers. Joining just-formed NASA at the end of the 1950s, he initially contributed to the development of the Redstone missiles for the Mercury Project, which lofted Alan Shepard into space in May 1961, just weeks after Gagarin.

But von Braun’s masterpiece was the colossal Saturn V. Standing 110 meters high and delivering 7.5 million pounds of thrust, it remains one of the most iconic machines of the Space Age. Thanks to the Saturn V, NASA carried out the Apollo program, and, on July 20, 1969, Neil Armstrong became the first human to set foot on the Moon, followed by eleven more astronauts across six successful landings. Later missions even carried lunar rovers, extending exploration across the dusty plains.

After Apollo, exploration drew back to Earth’s neighborhood. Low Earth Orbit (LEO), extending up to 2,000 km, became the human domain for the next fifty years. LEO’s proximity and Earth’s magnetic shield made it a natural choice for long-duration missions (see blog page Humans in Space for specific details).

In April 1971, a Proton rocket launched Salyut-1, the first space station. Two months later, Soyuz 11 docked successfully, a triumphal mission turned tragic when its crew perished during re-entry. The Soviet Soyuz system endured, later ferrying crews to MIR and the ISS space stations.

The United States followed with Skylab in 1973, using modified Saturn rockets and Apollo spacecraft. Instead of insisting on that technology, NASA developed the Space Transportation System (STS). Made of two boosters and a reusable orbiter (the Space Shuttle), the STS flew from 1981 to 2011.

The Shuttle made spaceflight routine, if never risk-free, and became the unrivaled transport king of LEO. In its 135 missions, it accomplished an extraordinary range of feats:

- Transported astronauts to MIR and later the ISS

- Deployed major observatories such as Hubble, Chandra, and Galileo

- Served as the carrier for the European Spacelab

- Became the workhorse for assembling the International Space Station

- Delivered and retrieved countless satellites, experiments, and technology demonstrators

After the Shuttle’s retirement, only Soyuz remained to transport astronauts to the ISS.

China, meanwhile, advanced its own human spaceflight: Yang Liwei flew on Shenzhou 5 in October 2003, and in 2012, taikonauts reached the first Tiangong station. The Shenzhou program, using Long March rockets and Soyuz-derived capsules, has since carried multiple crews to the modular Tiangong now in orbit. Its successor, the Mengzhou capsule, aims to bring the first taikonauts to the Moon and is planned for the end of the 2020s.

Reusability: Rockets that Come Back

Before May 2020, human spaceflight seemed destined to remain the preserve of governments. Then a private company rewrote the rulebook. SpaceX, founded by Elon Musk, had already proven itself in September 2008, when the Falcon 1 became the first privately developed liquid-fueled rocket to reach orbit. That breakthrough led to NASA contracts for cargo and eventually crew, restoring U.S. independence in getting astronauts to orbit.

Twelve years later, on May 30, 2020, the revolution became undeniable. Astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley lifted off from Kennedy Space Center’s historic Pad 39A atop a Falcon 9, inside the Crew Dragon Endeavour. They docked with the ISS after 19 hours, stayed for 62 days, and splashed down safely in the Atlantic. For the first time, a commercial company had carried humans to space and back.

Since then, Falcon 9 and Crew Dragon have made crewed launches a routine operation. The secret lies in reusability.

Falcon 9’s first stage lands back on drone ships or landing pads, refurbished and flown again. A booster now commonly flies dozens of times, slashing launch costs and creating an airline-like cadence.

In just five years, this system has built a track record once unthinkable, flying government crews, private explorers, and research missions alike:

- Demo-2: Bob Behnken & Doug Hurley, first commercial crew to the ISS, May 30, 2020.

- Operational NASA flights (Crew-1 through Crew-11, 2020–25): regular rotations of international astronauts to the ISS.

- Inspiration4: the first all-private orbital mission, circling Earth for three days, launched September 15, 2021.

- Axiom missions (Ax-1 to Ax-4, 2022–25): private crews visiting the ISS.

- Polaris Dawn: private mission testing new EVA suits and high Earth orbit, September 10, 2024.

- FRAM2 (2025): a private research flight, launched April 1, 2025, pushing Dragon into new territory, over Earth’s poles.

More than a dozen times, Crew Dragon has opened its hatch in orbit, not only for ISS operations, but also for private exploration. Space travel is no longer a rarefied endeavor; it is becoming increasingly repeatable.

First-stage reusability is the single biggest innovation in space transportation since the dawn of the Space Age. It is opening access to space wider than ever before, not only for agencies but also for private companies and, soon, ordinary citizens.

Spaceplanes: wings back in orbit

If Falcon 9 proved how powerful first-stage reusability can be, spaceplanes show what reusability looks like when applied to the second stage, the spacecraft itself. The archetype was the Space Shuttle orbiter, a winged vehicle that reentered and landed on a runway to fly again, carrying crew and cargo between Earth and orbit. It wasn’t the fully reusable two-stage system once envisioned, but it made the idea of a reusable spacecraft real and operational for three decades.

To see where that idea truly began, we step back even further, to drop-launch flight tests (a standard way in aviation to prove experimental vehicles safely). In the 1960s, the North American X-15 was carried to altitude under the wing of a B-52 and released before igniting its rocket engine. This method allows pilots to push into thin air at hypersonic speeds, then glide home to land.

The program set enduring marks: Mach 6.7 at over 102,000 ft, and 13 flights above 80 km (the U.S. astronaut-wings threshold), including two above 100 km (the FAI’s outer-space convention). That mix of air-launch, rocket boost, and runway landing foreshadowed modern spaceplanes.

Decades later, Burt Rutan revived the concept in the private sector with SpaceShipOne and its carrier aircraft White Knight, proving a small, winged, rocket-powered craft could cross the 100 km line and return to a runway, demonstrating this capability three times in 2004. Both vehicles were built and flown by Scaled Composites, Rutan’s company, and pilot Mike Melvil was awarded the title of first commercial astronaut.

That achievement inspired multi-billionaire Richard Branson to found Virgin Galactic, aiming to make space tourism a reality by launching ordinary people, though very wealthy, on suborbital flights. To pursue this dream, Virgin Galactic developed SpaceShipTwo and its mothership White Knight Two, with design heritage from Scaled Composites, manufacturing by The Spaceship Company, and operations under Virgin Galactic.

The program faced setbacks. The first SpaceShipTwo, VSS Enterprise, was lost in a tragic accident on October 31, 2014. But the second craft, VSS Unity, reached space in 2018 and went on to fly multiple suborbital missions.

In 2019, it carried Beth Moses, Virgin Galactic’s chief astronaut instructor, as the first passenger, and later welcomed paying customers. In July 2021, Unity also carried Richard Branson himself, fulfilling his dream of becoming an astronaut aboard his own company’s vehicle.

In June 2024, Unity performed its final commercial flight, Galactic-07, as Virgin Galactic paused operations to transition toward its higher-capacity Delta-class spaceplanes, now targeting service in 2026.

Spaceplanes also point back toward orbit. Dream Chaser, a lifting-body spaceplane from Sierra Space, returns to a runway at gentle ~1.5 g, ideal for fragile payloads. Its first vehicle, Tenacity, is a cargo variant for NASA’s CRS-2 missions; the inaugural ISS flight is currently targeted for Q3 2025 (with schedule risk), and a crew-capable version remains on the roadmap.

Europe is pursuing a smaller, uncrewed pathfinder: Space Rider, an ESA reusable lifting-body spacecraft that will launch on a Vega-C rocket. It is designed to stay in low Earth orbit for about two months before returning to a runway landing. Its maiden flight is currently expected in 2027, serving as a testbed that could inspire future crew-capable systems, even if none are officially planned today.

From B-52 drop-launches to Shuttle runways, from Unity’s suborbital arcs to Dream Chaser’s coming cargo hops, spaceplanes keep alive a simple, elegant idea: go up on a rocket, come home on wings. As first-stage reusability drives launch rates higher, reusable second-stage vehicles called spaceplanes are a way to make returns gentler, quicker, and ultimately more routine.

The New Race to Orbit and Beyond

A future rocket from the past, that is one way to describe NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS). Built from the legacy of the Space Shuttle, with engines, boosters, and design heritage directly recycled from the STS program, SLS is both a bridge and a reboot. It is a liquid-hydrogen, liquid-oxygen heavy-lift rocket, even more powerful than Saturn V, topped by the Orion spacecraft, capable of carrying four astronauts into lunar orbit.

The system already proved itself on November 16, 2022, with the uncrewed Artemis I mission. The next step, Artemis II, will fly astronauts around the Moon no earlier than 2026, followed by Artemis III, where the so-called Human Landing System (HLS) will take them to the lunar surface. Together, SLS and Orion form the backbone of the Artemis Program, an international effort to “go back to the Moon, this time to stay” (see the page A Moon of Opportunities for more details).

India contributes to space travel too, through the Ganganyaan Program. ISRO, the Indian space agency, identified its heavy launcher, the LVM3 (Launch Vehicle Mark-3), as the rocket for the program and adapted it for human flight, creating the HLVM3 (Human-rated LVM3). The Ganganyaan spacecraft consists of a crew and a service module, completely developed by ISRO.

A series of uncrewed missions has been carried out to test critical systems, and the first orbital test flights are scheduled for the coming years. Depending on the results, the first vyomanauts (vyoma means “space” in Sanskrit) are expected to reach orbit in 2026.

SLS and Gaganyaan are not the only future space travel systems in development. After the breakthrough of Falcon 9 and Crew Dragon, reusability has become the new gold standard in space transportation. The ability to land and relaunch rockets has transformed costs, cadence, and ambition, and no major player can afford to be left behind.

Around the globe, governments and private companies are working on their own reusable systems, hoping to close the gap with SpaceX and to secure a role in the next great chapter of space access:

- Blue Origin New Glenn: heavy-lift rocket, debuted on January 16, 2025, reaching orbit on its maiden flight. Crewed missions are not expected before the late 2020s.

- Europe’s Themis: a pathfinder for reusable first stages, with hop tests planned for 2025–26; an operational launcher could follow in the early 2030s.

- Rocket Lab Neutron: a medium-class reusable launcher, with its first flight targeted for 2025–26 from Wallops Island, Virginia.

- Russia’s Amur-SPG (Soyuz-7): a methane-powered reusable design in development; first flight not expected before 2028. Alongside it, the Angara A5 family continues testing (latest in 2024), while the Yenisei super-heavy remains a longer-term concept.

- China’s Zhuque-3: a private stainless-steel methane rocket aiming for first orbital flight in late 2025.

- China’s Long March 9: the state-led super-heavy reusable launcher, with an uncrewed debut around 2030 and a crewed lunar version in the early 2030s.

Last, the true game-changer the space economy is waiting for is Starship by SpaceX. First unveiled as the Mk-1 prototype on September 28, 2019, it looked more like science fiction than hardware. Yet in just four and a half years, after a string of spectacular tests and equally spectacular failures, Starship managed to reach orbital velocity and coast into space on March 14, 2024. Few projects in aerospace history have ever advanced at such a rapid pace.

The path has been anything but smooth: explosions on the pad, tanks collapsing, boosters lost at sea. But this was never a flaw; it was the method. SpaceX applied the same philosophy to Starship that made Falcon 9 successful: build fast, test hard, fail, learn, and repeat. Each wrecked prototype became data, each fireball a stepping stone. Where traditional aerospace waits for perfection on paper, SpaceX stacks steel, lights engines, and tries again.

That approach has already earned major institutional trust. NASA selected a dedicated version, the Starship HLS (Human Landing System), as the vehicle that will land Artemis III astronauts on the Moon. And in a historic first beyond the U.S., the Italian Space Agency (ASI) became the earliest non-American agency to sign for Starship, not for Earth orbit or lunar orbit, but for the Red Planet. Under this agreement, Italian scientific payloads will fly on one of Starship’s first commercial missions to Mars, marking the world’s first booked experiments bound for the red planet.

If Falcon 9 proved that first stages can return and fly again, and if spaceplanes showed that spacecraft themselves can be reused, then Starship is where the two approaches finally converge. It is designed as a fully reusable two-stage system, with both the booster and spacecraft forming a complete stack meant to launch, land, and launch again.

Starship aims to prove that rockets can not only return to Earth, but also continue to travel, from Earth to orbit, from orbit to the Moon, and from there to Mars and beyond. It is not just the next vehicle in the line; it is the bold leap the space economy is waiting for, the system that could turn exploration into settlement and dreams into infrastructure.

Beyond Chemical Propulsion, Further in the Solar System

Full reusability can transform the economics of spaceflight, but it doesn’t change the physics: all the vehicles we’ve covered still push against the limits of chemical propulsion. Chemical rockets can take us to the Moon and, at best, on long-duration missions to Mars. But to push human spaceflight beyond, to go faster, farther, and carry more, we’ll need new engines.

One of the most promising directions is nuclear propulsion. Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) heats propellant in a fission reactor and expels it through a nozzle, promising about twice the efficiency of top chemical rockets, enabling shorter Mars trips and heavier payloads. Nuclear Electric Propulsion (NEP) instead uses a reactor to generate electricity for high-efficiency thrusters, slower acceleration, but excellent endurance for cargo and deep-space missions. Both NASA and ESA are actively studying these technologies, though development paths are complex and programs have already seen delays and cancellations.

Another approach is plasma propulsion. Russia has tested laboratory prototypes of magnetic-plasma-accelerator engines, aiming eventually to cut Earth-to-Mars transits down to one or two months. These systems deliver very low thrust, but continuously, providing a steady push that becomes powerful over time.

A related concept is the VASIMR engine, developed by Ad Astra Rocket Company. It heats plasma with radio waves and channels it through magnetic fields, allowing thrust to be tuned, low and efficient for cruising, higher and more powerful for maneuvers. Tests on the ground have demonstrated tens of kilowatts of power; to truly enable fast crewed missions, VASIMR would require hundreds of kilowatts or even megawatts of electricity in space, likely from nuclear reactors.

And then there are the dreams. Warp drives, such as the Alcubierre concept, remain deeply theoretical, but they’re evolving. Recent research has gone beyond pure imagination, proposing numerical models that could satisfy energy constraints without resorting to exotic “negative energy.” Others have suggested ways to combine warp field metrics with wormhole geometries, or even hinted that curved spacetime near a black hole might reduce the exotic energy requirement.

While enticing, these ideas still confront formidable barriers, violations of energy conditions, the need for unobservable negative mass, and instability under quantum effects; so warp drives remain physics at its most speculative. Yet each new paper reminds us that imagination grounded in equations can open surprising avenues, even if the path remains decades or centuries away.

Even if those devices belong to science fiction more than to engineering, they remind us that imagination is always the seed of progress. From Icarus’ wings to Jules Verne’s cannon, dreams set the stage and lit the path. Then came the audacity to turn visions into reality, through the audacity and engineering genius of minds like Korolev and Musk. From the R-7 to Falcon 9, what once seemed impossible became real, and Starship may soon follow. After that, it could be the turn of nuclear engines and, one day, perhaps even warp drives.