The Moon for all, all for the Moon!

To fully enjoy reading this post, listen to Wind of Change by Scorpions and New Gold Dream by Simple Minds. Ideally, treat yourself and enjoy both, one after the other.

Why the Moon Matters

We were there 50 years ago. We visited its dusty surface for six crewed visits, then stopped. Why?

Mainly, the costs were unsustainable, the risks to human life were enormous, and the technologies were too complex to build and maintain for the long haul.

But the first Moon race was mainly fueled by opportunities. The Moon was a Cold War trophy, a way to showcase national strength, claim technological dominance, and shape global influence. Once the United States planted the flag and the Soviet Union stepped back, those opportunities seemed exhausted, and the focus shifted to Low Earth Orbit (LEO), offering many new benefits at a much lower cost.

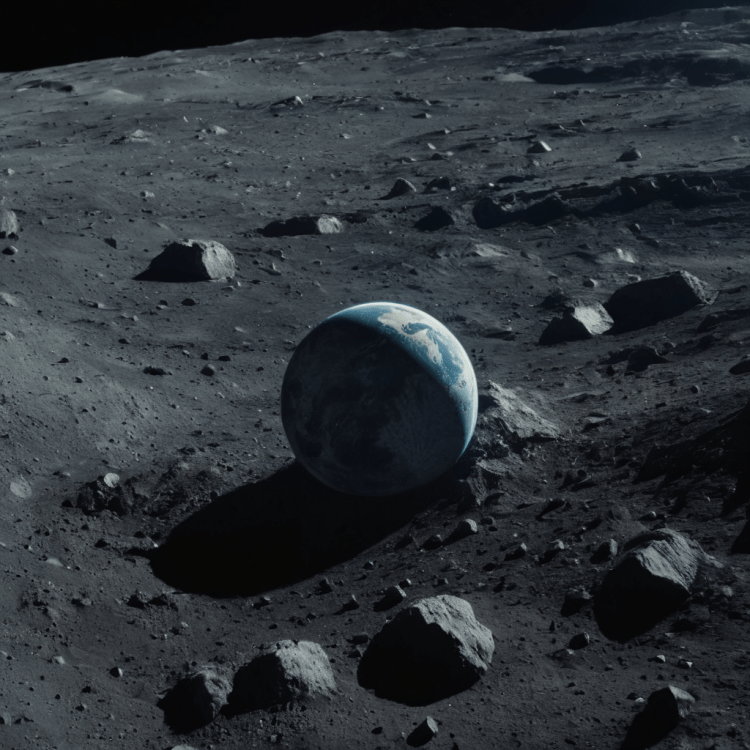

Now, we are looking at our natural satellite again with different eyes. This time, the motivations are broader and far more concrete. The Moon is close, resource-rich, and ideal as a proving ground for living and working off Earth. It is becoming a hub for science, exploration, and industry, and is increasingly seen as the gateway to Mars and the Solar System.

It is not just the United States that makes plans.

From the other side of the world, China is moving fast. It aims to land taikonauts, build a base at the Moon’s South Pole, and unlock key resources like water ice and Helium-3; India has already landed successfully near the South Pole; Russia is reviving its Luna program and collaborating with China; Europe is engaged through ESA, and Japan, the UAE, and others are steadily carving out their place in this new lunar chapter.

The world is heading for the Moon, and opportunities are again the driver.

Moon Exploration: Why it Started

The first Moon race was not just about planting flags. It was about prestige, establishing the best economic system, and the chance to lead the future. The Moon became a battleground for ideology and technological superiority.

The Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union pushed space exploration into overdrive. After early Soviet victories with Luna 2 and Luna 3, the Americans responded with an all-in strategy that culminated in the Apollo program. Landing a man on the Moon in 1969 was a masterstroke of soft power and a statement to the world: the U.S. was ahead.

Six Apollo missions reached the Moon’s surface between 1969 and 1972, with astronauts walking, driving, and golfing across the regolith. But once that symbolic victory was secured, interest quickly faded. The Soviets, having failed to send cosmonauts to the Moon, shifted focus to orbital stations, and the Americans followed suit. With no more geopolitical points to score, the Moon missions’ enormous cost and risk no longer seemed justified.

Instead, both powers began to look inward, investing in space laboratories in Low Earth Orbit, which offered new scientific returns at a fraction of the expense. (More on that in Humans in Space and Space Travel pages.)

Even after human landings stopped, robotic explorers kept the Moon within reach. The Soviet Luna missions returned samples and deployed the first rovers. Later, spacecraft from Europe, Japan, India, China, and others joined the quest, orbiting, photographing, and probing the surface in greater detail than ever. They scanned for water ice, tested landing systems, and laid the groundwork for today’s renewed interest.

Each mission, quietly and precisely, helped rebuild the path, revealing the Moon’s complexity, scientific value, and untapped opportunities.

The New Race to Exploit the Selenic Potential

The Moon is back in the spotlight for one reason: the opportunities it offers today’s world. Scientific, economic, and strategic interests are propelling a new wave of missions, ambitions, and investments, both from historic space powers and emerging players across the globe.

Alongside NASA and its Artemis program, new players like China, India, Japan, Israel, and the UAE are landing probes, testing technologies, and setting their sights on long-term goals. India landed successfully near the lunar South Pole with the Chandrayaan-3 mission. Japan’s SLIM and ispace missions are pioneering precision landings. China’s Chang’e program is evolving quickly toward human missions and infrastructure. And Europe is actively contributing through ESA, independently and in partnership with NASA.

What is changing is not just who is going, but why. The Moon is no longer a symbolic target. It is a proving ground. Its proximity to Earth, unique environment, and low gravity make it the perfect place to test new technologies for life support, resource utilization, and long-duration survival. It offers a stepping stone to Mars and beyond, helping us build the architecture of sustainable space exploration.

At the same time, the Moon holds tangible value beneath its surface:

• Water ice at the poles can be transformed into drinking water, oxygen, and hydrogen fuel

• The regolith could become building material for shelters and landing pads

• Metals and rare Earth elements may support in situ manufacturing or be sent back to Earth

• Helium-3 is a potential fuel for future nuclear fusion reactors.

According to the 2021 Lunar Market Assessment by PwC, the value of a functioning lunar economy could exceed 140 billion euros by 2040. That economy would be built around three pillars:

• Transportation of people and cargo between Earth, orbit, and the lunar surface

• Use of lunar data for science, technology, and media content

• Resource exploitation through mining, manufacturing, and infrastructure development

As access to the Moon increases, its ecosystem is expected to include space agencies, private aerospace firms, and companies from the mining, construction, robotics, and automotive sectors. These terrestrial industries may soon see the Moon as a natural extension of their markets.

All of this is already in motion. The technology is being developed. The partnerships are forming, and the vision is no longer science fiction.

The Moon is re-emerging not as a frontier to conquer, but as a platform to build from, a stage where economy, science, technology, and humanity all meet to shape the next era.

Legal Limbo: Rules, Loopholes and New Voices

International law is more about broad intentions than concrete rules when using the Moon. The backbone is the UN Outer Space Treaty of 1967, signed by the US, Russia, China, the EU, and other spacefaring nations. It sets out basic principles:

- Space is open to all nations and should benefit all humankind

- No part of outer space, including the Moon, can be claimed by any state.

- The Moon and other celestial bodies must be used for peaceful purposes, with nuclear weapons banned completely.

Inspired by the Antarctic Treaty, this framework aimed to avoid turning space into a new colonial battlefield. But there’s a catch: it’s very general. The Outer Space Treaty doesn’t define how to operate on the Moon or what to do with lunar resources. It left many questions unanswered: Who gets to operate on the Moon? Who owns the resources? How should profits be shared?

To patch this, the UN introduced the Moon Agreement in 1979. It proposed more detailed rules, including creating an international regime to govern lunar resources. It also proposed sharing the profits and the technologies behind space mining with developing countries. Sounds fair.

Not everyone agreed. Hardly anyone did. Only 18 countries ratified it, and none from the major space players. The reason? It was perceived as too restrictive, especially by nations banking on private-sector growth. Sharing technology and profits didn’t sit well with nations hoping to kickstart a space economy.

Instead, countries started crafting their space laws. These laws nod to the Outer Space Treaty but give companies more freedom. For example:

- The U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (2015) allows American firms to mine and own space resources.

- Luxembourg’s 2017 space law offers similar rights to companies, becoming a hub for space mining startups.

Investors saw a green light, resulting in a booming space economy built more on national interests than global cooperation. Is that a problem? Not really, since commercial players are accelerating much-needed innovation. But with no shared legal ground, tensions are bound to rise.

A new hope is coming from the next generation. The Space Generation Advisory Council (SGAC) is a global network of students and young professionals shaping the future of space. One of their teams, the EAGLE Action Team (Effective and Adaptive Governance for a Lunar Ecosystem), drafted a detailed proposal for a new Lunar Governance Charter. Presented to the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) in 2021, it called for peaceful and sustainable development on the Moon, built on consensus, not competition.

Has it been adopted? Not yet. But momentum is building. The COPUOS Legal Subcommittee convened in May 2025, marking a significant step toward establishing a legal framework for lunar activities.

A notable outcome was the presentation by the Working Group on Legal Aspects of Space Resource Activities of an initial draft set of recommended principles for space resource activities. This draft aims to guide the exploration, extraction, and utilization of lunar resources. Contributions come from over 20 countries, including China, the United States, Italy, and Luxembourg. The Moon Village Association also reported progress on the Global Expert Group on Sustainable Lunar Activities (GEGSLA), which seeks to develop best practices for sustainable lunar exploration.

These developments reflect a growing international consensus on the need for clear legal norms to govern long-term lunar activities, balancing national interests with collective responsibilities.

Meanwhile, another framework is gaining traction. NASA’s Artemis Accords offer a practical approach for cooperation in lunar exploration. While non-binding, they outline shared values and guidelines for countries joining the Artemis program (54 as of May 21, 2025). It’s not global law yet, but it’s fast becoming a bridge between ideals and operations.

Could this new framework be the spark that propels us beyond flags and footprints?

Artemis, Apollo’s Sister-Program

If Apollo was the symbol of Cold War triumph, Artemis is the promise of a new era, broader, more inclusive, and with deeper roots in collaboration. Named after the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology, the Artemis program builds on its predecessor’s legacy but aims for something more enduring.

On May 14, 2019, former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine announced the new Lunar endeavor, shifting from short-term visits to sustained presence. Its motto, “We’re going back to the Moon to stay,” signals the agency’s aim to build lasting infrastructure in lunar orbit and on the surface, paving the way for future Mars missions. More inclusive and collaborative than Apollo, Artemis brings international partners and commercial players together. This time, it’s not just a return, it’s a foundation for what comes next.

Recognizing the magnitude of this endeavor, NASA has partnered with international agencies, including the European Space Agency (ESA), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), Canadian Space Agency (CSA), Australian Space Agency (ASA), the UAE Space Agency, and Italy’s Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (ASI). They’ve formed a coalition under the Artemis Accords to promote peaceful and transparent lunar exploration.

In addition to international collaboration, NASA has enlisted commercial partners for specific mission components:

- SpaceX and Blue Origin have secured contracts to develop the Human Landing System (HLS), facilitating astronaut landings on the Moon.

- The Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program engages companies like Astrobotic, Intuitive Machines, and Firefly Aerospace to deliver scientific instruments and technology demonstrations to the lunar surface, paving the way for future crewed missions.

The CLPS program is NASA’s bold bet on leveraging private innovation to support lunar exploration. Instead of bringing instruments and tech payloads to the Moon directly, it contracts commercial providers to deliver them. The journey so far has been anything but smooth, but that’s exactly the point. Pioneering efforts are expected to be hard.

The first CLPS flight, Astrobotic’s Peregrine Mission One, launched in early 2024 but didn’t reach the lunar surface due to a propulsion system failure. Soon after, Intuitive Machines’ IM-1 mission achieved a historic but challenging soft landing (the first by a U.S. spacecraft in over 50 years), though with limited functionality after touchdown. Its follow-up, IM-2, encountered difficulties and did not meet all mission objectives at the Lunar South Pole. Meanwhile, Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost Mission 1, targeting Mare Crisium, delivered its payloads successfully and marked a strong debut for the company and the program.

Despite early setbacks, CLPS is moving forward with an ambitious schedule. The second half of 2025 is expected to feature Blue Origin’s Mark 1 Pathfinder Mission, Intuitive Machines’ IM-3, and Astrobotic’s Griffin Mission 1, each carrying critical science and tech payloads. Looking ahead to 2026, Blue Ghost Mission 2 and Astrobotic Mission 3 are already developing, continuing NASA’s push for regular, cost-effective access to the lunar surface.

Even when missions fail, each contributes vital experience in navigation, thermal protection, autonomous landing, and lunar operations. Together, they’re building the backbone of a future commercial logistics network and proving that opening the Moon to industry is not just possible, but already underway.

While commercial players help build the path, NASA continues to develop the core systems that will carry astronauts to lunar orbit and back:

- The Space Launch System (SLS): NASA’s powerful rocket is designed to transport astronauts to lunar orbit.

- The Orion spacecraft: A capsule that will carry astronauts from Earth to lunar orbit and back.

- The Lunar Gateway: the Moon orbital station hosting astronauts for scientific research and allowing them to reach the surface on a landing system developed under the HLS program

Financially, the Artemis program has been a significant investment, with a budget of $53 billion allocated for 2021–2025. However, recent developments indicate potential shifts in funding priorities. The proposed 2026 NASA budget suggests substantial cuts to programs like the SLS and Orion, favoring commercial alternatives and reallocating resources towards Mars exploration. This proposal also includes terminating the Lunar Gateway after Artemis III, signaling a strategic pivot in NASA’s long-term exploration plans.

Mission Timeline:

- Artemis I: Launched on November 16, 2022, this uncrewed mission tested the SLS and Orion systems, successfully returning to Earth on December 11, 2022.

- Artemis II: Now scheduled for April 2026, this mission will carry astronauts around the Moon without landing. The crew includes NASA astronauts Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Hammock Koch, and CSA astronaut Jeremy Hansen.

- Artemis III: Aiming for a 2027 launch, this mission plans to land astronauts near the Moon’s South Pole, utilizing a modified SpaceX Starship as the landing vehicle.

Artemis IV and V: Initially planned to expand lunar exploration and establish the Lunar Gateway, these missions face uncertainty due to proposed budgetary changes.

While the future of the Artemis program is subject to political and fiscal dynamics, the commitment to returning humans to the Moon remains a central goal for NASA and its partners. The evolving landscape underscores the importance of international collaboration and adaptability in the pursuit of space exploration.

The Other Side of the… Moon

While the Artemis program has gathered support from over fifty countries, not everyone sees it as the best path forward. In 2020, then-Roscosmos chief Dmitry Rogozin dismissed Artemis as a “political project” aligned with Western interests, likening it to NATO and criticizing what he saw as a departure from the collaborative spirit of the ISS. With the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, nearly all space cooperation between Russia and the West came to a halt, and the International Space Station became the last active bridge.

But Russia didn’t step away from the Moon. It simply looked East.

Already emerging as a dominant space power, China deepened its partnership with Russia in space and geopolitics. Unlike Artemis, China’s lunar strategy unfolded with fewer speeches and more results. Through its ambitious Chang’e program, China has developed:

- The Long March 5 rocket, already capable of sending payloads to the Moon

- A next-generation crewed spacecraft, currently in testing

- Chang’e-4, the first and only mission operating on the far side of the Moon

- Chang’e-5, which returned lunar samples to Earth in 2020, the first time in over 40 years

- Chang’e-6, launched in May 2024, successfully collected and returned nearly 2 kilograms of samples from the Moon’s far side, a global first

A roadmap that continues with Chang’e-7 (2026) and Chang’e-8 (2028), focused on prospecting for resources and building the first robotic outpost near the lunar South Pole.

Human landings are planned by 2029–2030, following a step-by-step approach: first robotic infrastructure, then taikonauts.

Meanwhile, Russia’s Luna-Glob program aims for similar goals but has moved more slowly. Luna-25, its first return to the Moon in decades, launched in 2023 but failed during descent due to a navigational error. Future missions, Luna-26 and Luna-27, are tentatively planned for 2027 and 2028. A collaboration with China may provide a much-needed boost.

In 2021, China and Russia signed a Memorandum of Understanding to create the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), a permanent base near the South Pole, designed for science, resource utilization, and long-term habitation. As the name indicates, this project is not closed. China and Russia have stated that the ILRS is open to international partners, even extending invitations to ESA and other nations.

This presented a unique opportunity for Europe to collaborate with Western countries on the Lunar Gateway while participating in a surface base with China and Russia. It could have been a strategic bridge between the two blocs, a rare space for diplomacy. But the war in Ukraine shattered that possibility.

What remains is a tale of two visions: Artemis, with its open, multinational architecture, and the ILRS, rising from the East with a slower but determined pace. Both are heading for the same destination: the Moon’s South Pole. Why? Because that’s where the future is being built, where water, resources, sunlight, and strategic value converge.

Because that’s where the opportunities are.

The Final Push: from Plans to Real Actions

Over the past decades, we’ve witnessed a resurgence in lunar exploration, driven by scientific curiosity, economic potential, and strategic interests. International collaborations have laid the groundwork, with programs like Artemis, Chang’e, and Luna-Glob marking significant milestones. Legal frameworks are evolving, aiming to govern activities on the Moon responsibly. Yet, as we stand on the cusp of establishing a sustained human presence on our celestial neighbor, critical challenges remain, particularly in technology, collaboration, and funding.

Which technologies are critical to making a stable lunar presence a reality?

Establishing a permanent foothold on the Moon demands advancements across multiple technological domains:

- In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU): Harnessing lunar resources is pivotal. Technologies are being developed to extract water ice for life support and fuel, and to utilize regolith for construction materials, reducing reliance on Earth-based supplies.

- Radiation Protection: The Moon’s lack of atmosphere exposes inhabitants to harmful cosmic rays and solar particles. Innovations like the LURAD radiation monitoring system are essential for ensuring astronaut safety.

- Habitat Construction: Developing habitats that can withstand extreme temperatures, micrometeorite impacts, and lunar dust is a priority. Concepts include inflatable structures, habitats protected using 3D-printed regolith, and settled in lava tubes.

Autonomous Robotics: Given the Moon’s harsh environment, autonomous robots are crucial for tasks ranging from site preparation to maintenance, minimizing human risk. - Sustainable Energy Systems: A Continuous power supply is vital. Solutions like the Lunar Vertical Solar Array Technology (VSAT) are being explored to provide reliable energy during the lunar day and night cycles.

While technological strides are being made, funding and international collaboration present both opportunities and challenges:

- NASA’s Budget Cuts: Recent proposals suggest a 24% reduction in NASA’s budget, potentially impacting key programs like Artemis and the Gateway. This has raised concerns about the U.S.’s commitment to lunar exploration.

- ESA’s Pivotal Role: In light of U.S. budget uncertainties, the European Space Agency is evaluating its position, potentially stepping up to lead initiatives like the Gateway, ensuring continuity in lunar missions.

- China’s Steady Progress: Contrasting the U.S., China continues to advance its lunar ambitions, with successful missions like Chang’e 6 and plans for a lunar base in collaboration with Russia, highlighting a shift in global space leadership.

Geopolitical tensions and shifting international dynamics could lead to new alliances, including with rising space actors like the Arab nations. With eyes on diversifying beyond oil and seizing lunar opportunities, they may become key investors and partners in the next wave of space development.

Beyond the technical and political realms, the renewed focus on the Moon heralds a cultural transformation. The prospect of living and working on the Moon inspires a new generation, blending science fiction with tangible reality. As we prepare to become spacepolitans, citizens of both Earth and space, the Moon serves as our stepping stone into the broader cosmos.

Against all odds, the momentum toward a sustained lunar presence is undeniable. The Moon beckons not just as a destination, but as the new reachable frontier for humanity’s collective aspirations.