Building beyond Earth is the key to the human future in space and the rescue of natural life on our home planet. It sounds so Spacepolitan.

Listen to Gravity by Lacuna Coil to enjoy reading this post.

Introduction – Why Build in Space?

Since the dawn of space exploration, everything we have sent beyond Earth has been built on the ground. However, launchers impose strict limits on weight and dimensions, forcing us to construct large structures —like space stations— module by module, assembling them in orbit. In-space manufacturing could change this paradigm.

Initially, we would still need to transport semi-finished products from Earth, but finalizing them in orbit could bypass further size constraints. The following step? Establish orbital factories to process raw materials from Earth and recycle what is already available in orbit. This would unlock space’s unique advantages: microgravity for precision manufacturing, continuous solar energy for power, and an environment free from contaminants that can interfere with delicate processes.

Eventually, mining and refining raw materials directly in space would close the loop, enabling self-sustaining construction beyond Earth’s surface. This could support everything from building space infrastructure to producing spare parts to repair facilities and even manufacturing goods for Earth, the Moon, or Mars, ushering in a new era of space logistics and starting the first space circular economy.

How far are we from this vision? It may seem distant, but progress is accelerating, and the foundations of this future are already being laid.

A Look Back – Historical Milestones in Space Manufacturing

Guess who was the first to carry out a “build” activity in space? The Soviets, of course. In 1969, during the Soyuz 6 mission, cosmonauts Georgi Shonin and Valeri Kubasov performed welding experiments using the Vulkan device, proving that orbital welding was feasible. The electron beam was the most successful of the three types of welding tested (low-pressure compressed arc, electron beam, and arc with a consumable electrode). This marked the first-ever metalworking in space, a key milestone for future in-space manufacturing.

The Americans followed with their first basic material experiments on the Apollo capsules and, during the Skylab era (1973-79), with more complex experiments on metals, including welding, brazing, and melting. On board the Skylab, Americans used the M512 Materials Processing Facility to grow crystals in space, providing the first results of the advantages of producing crystals in the microgravity environment, without having to deal with gravity. The Soviets reached the same outcomes during the Salyut program, particularly with the Soyuz 21 mission on board the Salyut 5 station, using the Kristall furnace to “cook” their crystals.

In addition to metals and chemical substances, the first human outposts in space supported experiments on various plants, from onions to rice to flowers. The first was the growth of some Arabidopsis, a true “role model” for plant biology, on board the Salyut 7 in 1982.

During the Space Shuttle and MIR time, experiments multiplied in every field of space production. The Wake Shield Facility, an experimental science facility onboard the Shuttle, was used to exploit another benefit of space: the vacuum condition. NASA scientists used the Wake Shield Facility to grow the first-ever crystalline semiconductor thin films in the ultra-vacuum of space with outstanding results. The “new” Kristall module on the MIR station hosted several furnaces for experiments, such as the Krater 5, which was used for processing semiconductor materials.

The International Space Station (ISS) has been the perfect ground for countless in-space manufacturing and production experiments. 3D printing technology changed everything, introducing the possibility of creating objects in space. The first zero-g 3-D printer was built by Made in Space Inc. (now part of Redwire Space) and installed on the ISS on November 14, 2014. The first plastic object was produced some days after, on November 24, and it was a faceplate of the extruder’s casing of the printer itself.

From Experiment to Production – The Dawn of In-Space Manufacturing

3-D printing evolved on the ISS, thanks to:

- The Additive Manufacturing Facility by Made in Space, capable of using different kinds of plastics

- The Ceramic Manufacturing Module by Made in Space to print objects out of ceramic;

- The Metal 3D Printer by Airbus Defense and Space with the first metal object produced in space in 2024.

Other productions tested recently on the ISS have been optical fibers, ZBLAN fibers in particular, and protein crystal growth, which are relevant to unlocking the creation of new drugs in microgravity. Not to forget: astronauts growing and eating various vegetables and the first 3D printing of human meniscus tissue.

Meanwhile, aboard the Chinese orbital station Tiangong, other experiments have been run to test material properties in microgravity and prepare to develop in-space manufacturing: welding, crystal growth, 3-D printing, and even material recycling. China is ramping up very fast to make in-space production a new routine.

Private companies are entering the field as well! Varda Space Industries was the first to “cook” crystals of the Ritonavir drug in orbit aboard its Winnebago space factory capsule, capable of returning the product to the ground in 2024. Winnebago was launched twice again in 2025 and it is just the beginning. But it’s not an isolated case. Companies like ATMOS Space Cargo, Space Cargo Unlimited, and Space Forge will send their first space factory prototype into orbit in 2025, marking the beginning of commercial in-space production!

Driving the Industrialization of Low Earth Orbit

For more than fifty years, in-space manufacturing experiments have been run to learn the behavior of materials in space. Technologies have been demonstrated, and scientists have studied how to weld metals, 3-D print and grow crystals, proteins, and even plants in microgravity. So, we know how to produce in space.

What makes space production, particularly in Low-Earth Orbit, more interesting from a financial, so-called commercial point of view? Cheaper access to space (see reusable rockets) is opening space for many new ventures, including goods production.

Microgravity’s unique advantages have begun to be attractive for commercial exploitation. The advanced materials industry wants to produce ZBLAN fiber optics and semiconductor crystals in space to benefit from their fewer defects and enhanced purity. Space ZBLANs could increase communication bandwidth, which is hardly possible with products made on Earth, while new semiconductor wafers enable the next-generation electronics needed for applications like AI.

Pharma is eager to create new proteins with structures not allowed by gravity and biotech to modify plants’ DNA using the harsh environment of space as an accelerator, avoiding direct genetic manipulation. The space proteins will enable the creation of new kinds of drugs, specifically targeting the antagonist molecules of a disease, while plants modified in space could improve the crops’ yield without using the same amount of chemicals, like pesticides and fertilizers.

Getting Products Back – The Logistics Challenge

If launching objects in orbit is hard, bringing products safely on the ground is even harder. From Low-Earth Orbit, the heat generated during atmospheric re-entry could lead to temperatures over 3.000 °C. The return vehicle should deal with it without damaging itself and its cargo. After surviving the re-entry, it must land safely in a designated zone, determined to get the re-entry license ahead of the landing.

Aerospace engineers developed different solutions to overcome this double challenge. The high-temperature problem has been addressed with thermal protections, like heat shields. Made of various materials, they are usually placed on one side of the vehicle and exposed to the atmosphere’s impact. The precise and safe landing has been addressed in almost two big categories: capsules, slowing down with parachutes, and practically no possibility of maneuvering, and space planes, decelerating thanks to the atmospheric drag and gliding like an airplane. Cross-overs between the two were developed too.

To make things even more complicated, astronauts have run or overseen most of the manufacturing in space so far. As humans, they need life support systems and extra safety measures that cost in weight and size, as well as money. This is still a huge obstacle to scaling production, limiting the activities to experiments and technology demonstrators.

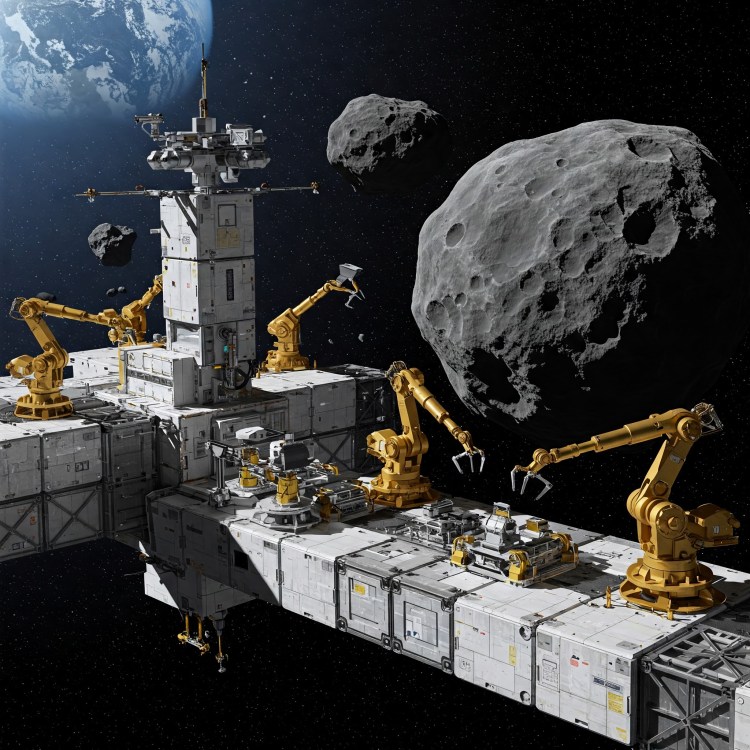

The solution is obvious but not as easy as it sounds: eliminating the human factor and introducing fully automated factories. Those robotic platforms should be able to handle all the production operations, and possible off-nominal situations, fixing eventual issues that might occur.

An experimental automatic orbital farm has already been tested and is now on its third flight in space: Winnebago by Varda Space, cited above. Others are coming soon in 2025 and, guess what, they are all European. The first to launch will be ATMOS’ Phoenix, with its futuristic inflatable heat shield. Space Cargo Unlimited’s Bentobox will follow with its capacity of hosting payloads with different requirements of power, temperature, pressure, and more. SpaceForge’s ForgeStar-1 will join the returning factories fleet, supporting pharma and semiconductor production.

From LEO to Deep Space: Building a Space-Based Economy

Let’s move to the potential future scenarios for in-space production. The natural evolution of temporary (they launch and land) space factories could evolve into permanent orbital facilities, with materials and goods moving back and forth thanks to space freighters as today with the International Space Station and the Tiangong station. They could be attached to current and future space stations (like Orbital Reef or Starlab) or be fully autonomous and standalone. In one way or another, decoupling the production platform from the logistic vehicle will increase its dimensions and output per flight, a crucial factor for its profitability.

As orbital production becomes routine, the next logical step is establishing similar platforms around the Moon and Mars. These platforms could provide products including food to ground bases, reducing reliance on Earth and enabling colony expansion. Production could be moved to the Lunar and Martian surface, to allow in-situ resource utilization and the expansion of the bases themselves.

Demand for raw materials will rise as off-world production scales, making asteroid mining an attractive solution. As discussed in the section about asteroids, space rocks are rich in ore, carbon, water ice, and other materials, useful for construction, semiconductors, water processing, and even fuel refining. They could be our mines in space, providing raw materials for any kind of in-space manufacturing.

Mining, farming, manufacturing, and consumption are the pillars of the circular space economy, and in-space production is its engine, the key to making it a reality. Without it, space mining would be futile, and off-world consumption unfeasible. In-space production is the key to achieving the utopia of the Spacepolitans Manifesto: making the Earth a planetary natural park and expanding humanity all over the Solar System.